August 2010 Archives

We can take one further step toward finding common ground in my ongoing debate with Drs. Pies and Zisook. Dr. Pies has helpfully pointed the way in his latest piece, which can be retrieved here.

We agree that the problem is the fuzzy boundary between normal grief and Major Depressive Episode (MDE). It is at this mild end that our dispute lies. There is no dispute at the severe end - severe depressive symptoms during bereavement are already meant to be diagnosed as MDE using the current guidelines in DSM-IV-TR. So the test case is someone who has lost a spouse or child and has just two weeks of sadness and loss of interest, appetite, sleep, and energy. Such a person would have to be diagnosed with MDE if we were to follow the DSM-5 suggestion to simply remove the Bereavement exclusion.

Dr. Pies and I both disagree with the DSM-5 suggestion that two weeks is a long enough duration. There is no research suggesting that the distinction between normal grief and mild MDE can be reliably and validly made so early after the loss of a loved one in a griever with such mild and ubiquitous symptoms. This level of mild symptoms for this short a duration occurring in the immediate aftermath of a loss are just too common and too compatible with normal grief to be considered MDE.

Dr. Pies and I also agree that there is no need to medicate this griever having mild and completely expectable symptoms for so short a period. We would both instead recommend a combination of commiseration, empathy, support, and watchful waiting to see if the person goes on to have a normal evolution of grief (most will) or goes on to have enduring or more severe symptoms compatible with MDE.

Dr. Pies worries more than I do that the current DSM-IV-TR criteria are too stringent and create a false negative problem- ie missing MDE during bereavement and witholding appropriate treatment from those who need it. He would make it easier to get an MDE diagnosis during bereavement than is currently possible using DSM-IV-TR, but would require much more stringent standards for its diagnosis than are being suggested for DSM-5. Dr. Pies suggests a one month duration (not two weeks) and perhaps a higher threshold of symptom severity.

Dr. Pies' suggestions are a reasonable way to balance the risks of false negatives vs false positives. I worry much more than he does about false positive overdiagnosis and overtreatment. So I would prefer to stay where we are, but I could not strongly disagree with the Pies/Zisook suggestion. I would add to it just two exclusions. The diagnosis of MDE may be inappropriate if the individual's culture calls for a more profound expression of grief or if the individual has a personal history of a deep, but self limited, grief in the past.

So, where do we continue to disagree. I believe that to remove the Bereavement exclusion for MDE would disastrously open the floodgates to the misdiagnosis and overtreatment of normal grief (especially by hurried primary care physicians who do much of the prescribing). To me, the DSM-5 suggestion, as it stands now simply doesn't fly at all and is a public health threat. In contrast, Dr. Pies is willing to hold his nose and swallow a DSM-5 suggestion that he acknowledges will confuse grief with MDE. He invokes the image of saved suicides to defend his persevering effort to not miss any MDE patient, regardless of the negative consequences.

I analyze the benefits and risks of the DSM-5 proposal quite differently. I don't see much benefit because I don't think the current rules result in many missed cases. DSM-IV-TR already allows extremely wide play for clinical judgment in deciding between grief and MDE. A clinician is welcomed to make an MDE diagnosis whenever he believes the specific circumstances warrant it -- even with relatively mild symptoms in a grieving person (say someone who has had previous depressions or previous prolonged grief). If the grief symptoms are severe, DSM-IV-TR insists that MDE be diagnosed. Clinicians do not find impediments to the appropriate diagnosis under the current system. It is an unproven and unlikely red herring that the DSM-5 change will save lives (or for that matter have any beneficial effect at all).

But, as detailed in several previous posts, I believe the risks of the suggested change are great. I won't go through all the specific arguments yet again, but DSM-5 is promoting a needless expansion of psychiatric diagnosis that would reduce the dignity of grief, create insurance and job stigma, and result in unnecessary, expensive, and potentially harmful treatment.

There is no proven efficacy for medication treatment given after just two weeks of mild symptoms in grievers. My guess is that the placebo response rates would be so high in this population that no active medication efficacy could ever be demonstrated. But medications do have side effects (including increasing suicidal symptoms in some people).

My suggestion to Pies/Zisook is to not give up the fight with DSM-5 for an appropriate one month duration requirement for milder MDE -- if not in all situations (my choice and theirs) then at least for MDE during bereavement. Swallowing a spoiled half loaf can be bad for the nation's health. We can assume that drug advertising to patients and marketing to doctors will result in a flood of treatment that they would also question. This should worry Pies/Zisook more than it does and stiffen their resolve to fight the good fight (with an admittedly unreasonable DSM-5) to require a one month duration of symptoms.

So let's be clear about a reasonable compromise. Reasonable people can disagree about the precise duration requirement before grief can be considered mild depression. Pies/Zisook suggest one month. I am OK with the DSM-IV-TR two months. Some people think it should be longer. No one but DSM-5 is suggesting two weeks- which seems like a really bad idea.

This ongoing Talmudic debate with Pies/Zisook has been fruitful. A similarly careful risk/benefit analysis should be, but is not, occurring for all of the many questionable DSM-5 proposals.

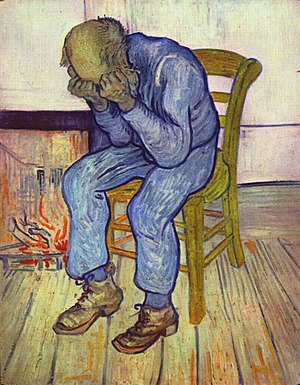

Image via Wikipedia

On August 15, I published an op-ed piece in The New York Times expressing the view that normal grief is normal and should not be confused with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD). The DSM-5 suggestion to remove the bereavement exclusion for MDD would convert grief after losing a loved one into mental disorder. Two short weeks of expetable symptoms like sadness, insomnia, difficulty working, and loss of interest, appetite, and energy would qualify for an MDD diagnosis. This mislabeling would then often trigger stigma and unnecessary medication treatment. More details can be found in the op-ed piece itself or on previous numbers of this blog.

On August 20, the Times published a number of letters taking all sides on the issue. There were two rejoinders to my view that I believe are misleading enough to require comment:

Counter Argument 1: Patients experiencing a well-established Major Depressive Episode (MDE) beginning during bereavement are no different in presentation and treatment response than those whose MDE follows after other severely stressful life events.

Reply: True enough, but totally irrelevant to my concern. Well established MDD is not in question (it is already diagnosable in DSM- IV-TR). The respondents continue to confuse the issue by focusing only on the already well established cases of MDD with a duration in studies usually greater than two months These are the true positives and there is no controversy whatever regarding their diagnosis. Well established (i.e. severe or enduring) MDD during bereavement has never been the issue.

It is the false positives I worry about -- those with normal and time-limited grief that will remit in the natural course of things without diagnosis or treatment. Two weeks is far too short a duration when we are considering relatively mild symptoms that are so intrinsic to grieving. Rushing to judgment that a mental disorder is present will lead to remarkably high false positive rates and transform normal grief into a medical disorder.

Counter Argument 2: The respondents claim that the DSM-5 intention is only to diagnose MDD, not to include normal grief.

Reply: The crucial and clinching point is that these are clinically completely indistinguishable at frequently encountered levels of normal grief. Prospective studies show that almost half of all the bereaved reach MDE two-week symptom thresholds sometime during the first year after their loss, usually within the first two months. I challenge anyone to distinguish clinically between two weeks of normal grief and two weeks of mild MDD under these circumstances. I certainly can't make this distinction, I very much doubt that my respondents can, and I feel sure that primary care physicians can't manage it while seeing a grieving patient in a seven minute evaluation.

Distinguishing grief from MDD is no problem when symptoms become severe or are enduring. DSM-IV-TR already recognizes this. It allows the diagnosis of MDD anytime during bereavement when there is suicidality, psychosis, morbid worthlessness, psychomotor retardation, or inability to function. This is meant to encourage early diagnosis and active psychiatric intervention whenever this is needed. There is no compelling problem that needs fixing. Grieving patients who need psychiatric help already get it.

Before jumping the gun to a premature and potentially harmful diagnosis, why not watchfully wait a few more weeks to determine if the grief is severe and enduring enough to warrant the label of mental disorder. To do as DSM-5 suggests would instead mislabel a substantial portion of normal grievers and would inappropriately stretch the boundary of psychiatry by medicalizing grief.

The furor surrounding the recently proposed Alzheimer's Guidelines was provoked by their premature attempt to introduce early diagnosis, well before accurate tools are available. The same laudable but currently clearly unrealistic ambition has propelled two of the worst suggestions for new diagnoses in DSM-5: Psychosis Risk, Mild Neurocognitive.

The concept of early identification and intervention is understandably appealing. The problems that eventually blossom into full-fledged psychiatric disorders do not arise suddenly and de novo. Undoubtedly, they have had a long history of gradual stages with changes that at first cause no symptoms whatever, followed by mild premonitory symptoms, followed by the full blown disorder. Clearly, it would be wonderful to prevent the progression and its consequent mounting damage by intervention at the earliest possible moment. Accurate early diagnosis followed by effective early treatment would reduce the direct burden of illness and also its secondary negative consequences.

Optimists among the proponents of preventive psychiatry point to the trend throughout medicine to catch disease earlier and intervene more aggressively. Without going into the merits and risks of early screening in medicine (which remains a mixed and highly controversial issue), the analogy simply doesn't fly. Early diagnosis in psychiatry currently lacks any tools to be helpful and may instead, in its well-intentioned and unwitting way, be extremely harmful both to the individual patient and to public policy.

Preventive psychiatry would have to rest on six foundations: 1) a method of diagnosis that is accurate even in the early stages of the disorder; 2) a treatment that is effective in improving early symptoms and in preventing their progression; 3) a treatment that is safe even if provided over the necessary course of what may be many decades; 4) a manageable degree of stigma, worry, and disadvantage from gaining a label that implies risk and progressive impairment; 5) a favorable risk/benefit analysis regarding clinical utility; and 6) a reasonable public policy cost/benefit analysis. Let's see how the psychosis risk and mild cognitive disorders stack up on these necessary benchmarks:

On diagnostic accuracy: neither proposed disorder has a diagnostic measure that is accurate. Psychosis risk has a false-positive rate of 70-90%. Laboratory studies for mild cognitive are still in very early stages of testing.

On treatment efficacy: None proven for either disorder.

On treatment safety: antipsychotic medications likely to be used for psychosis risk frequently produce enormous weight gain and its dire complications.

On stigma and worry: considerable for both. The power to label could here be the power to destroy.

On clinical utility: none for either. It is all risk and no current gain.

On public policy cost/benefit: especially unfavorable for minor cognitive disorder given the very expensive imaging studies and the lack of any clinical benefit.

Before their suggestions will make any sense, the experts in schizophrenia and dementia who are pushing for earlier diagnosis need first to do the research to fill in all the above blanks. Most likely this research enterprise will take a decade (and possibly much more). Until then, caution is safer than wishful thinking.

In July, panels sponsored jointly by the National Institute of Aging and the Alzheimer's Association presented controversial proposed guidelines for diagnosing Alzheimer's at three different stages of its progression: 1) preclinical, 2) mild cognitive impairment, and 3) classic dementia.

The preclinical panel stated that laboratory testing (i.e. PET or MRI scans, spinal taps, or blood tests) before the appearance of symptoms was meant to be purely for research. But, the other two panels seemed to suggest that laboratory testing was ready, or soon would be ready, to be used in routine clinical practice in diagnosing mild cognitive impairment or dementia. Faced with widespread skepticism, the panels held a conference call yesterday to clarify their position. As reported by Gina Kolata in The New York Times, there is reassuring new information. The panels recognize that laboratory testing is still only a research tool and will not be recommending that it be included as part of current clinical diagnosis. This makes great sense. All the available tests are at an early stage of development and are not nearly ready for routine use.

Rapid strides are being made in the study of Alzheimer's disease, with powerful new methods leading us closer to understanding its causes and mechanisms. But let's not jump the gun and mislead ourselves or the public into the false beliefs that a diagnostic breakthrough has already been made and that a treatment breakthrough is possible in the near future.

It is pretty easy to show that a promising laboratory procedure yields different group mean values when comparing Alzheimer's to a control group. It is very difficult to prove that it has sufficient reliability, accuracy, clinical utility, and cost effectiveness to become a useful diagnostic test worthy of use in routine clinical practice. It will require years of testing in very varied populations before we will learn if any of the currently available candidates is indeed the long awaited diagnostic test for Alzheimer's.

It is understandable that Alzheimer's experts have a strong desire to become preventively proactive. Can amyloid be the early marker of Alzheimer's, in analogy to cholesterol and heart disease? Can early identification and early intervention prevent the ravages of the disease? The problem is that you simply cannot skip the middle steps. Do the research first, then publish the guidelines.

And we should also be cautious in our expectations for a treatment breakthrough. It is possible that learning more about the mechanisms of Alzheimer's may eventually lead to the development of a rational cure or preventive, but it is equally possible that it will not. The general experience in medicine over the past three decades is that an exponential explosion in knowledge about a disease does not often lead to any immediate miracle cure. Moreover, the lack of success to date in developing medications for Alzheimer's does not inspire confidence. The available drugs -- although they have been highly profitable to the drug companies -- have little, if any, efficacy for patients. Attempts to develop a new generation of effective drugs have so far failed despite considerable investment. There does not appear to be any low-hanging fruit.

We should have and encourage reasonable hope regarding advances in Alzheimer's, but should avoid hype and hoopla. Progress will be steady, but probably much slower than suggested by the recent excitement.

The DSM-5 first draft has proposed many new diagnoses that would create enormous problems (especially false-positive "epidemics" and forensic misuse). Two perceived needs have driven the DSM-5 Work Groups in this unhappy direction:1) therapeutic zeal not to miss patients who might benefit from treatment; and 2) an aversion toward using the Not Otherwise Specified (NOS) categories. I will argue that these NOS categories impart a great deal of useful clinical information and are essential to the flexible and effective use of the manual. Giving every presentation a specific name and code in order to reduce the use of NOS would create much worse problems than it would solve.

The common prejudice against NOS diagnosis is that it puts psychiatry in a bad light. Why should as many as a third of our patients not qualify for anything more definitive? How do we explain this to them, their families, to referral sources, and to ourselves? How can we plan a specific treatment if the patient doesn't have a specific diagnosis? And so on. It may be useful to answer these questions in the act of exploring the different ways patients actually qualify for a NOS diagnosis:

1) There is simply not enough information to be more specific. Sometimes, this occurs because there was insufficient time for a complete evaluation or the patient is uncooperative and there is no informant or chart. Often, though, it comes from the inherent uncertainties of the situation. I have, for example, rarely felt comfortable with any label other than Psychotic Disorder NOS for psychotic teenagers who have only short track records. There is usually just too much uncertainty about the etiology (e.g., role of drugs) and their future course to be more definitive. There is nothing to be defensive about in using NOS in these situations. The designation Psychotic Disorder NOS conveys a great deal of information, while keeping tentative what deserves to be kept tentative. The immediate treatment target is clear without imposing a premature closure on long term treatment needs or prognosis. This can easily and productively be explained to patients and families.

2) The presentation clearly belongs in the section, but does not fit the prototype of any of the specific disorders defined there. For example, in DSM-IV we included binge eating disorder as an example of Eating Disorder NOS, rather than elevating it to a separate coded category. This allows the clinician the flexibility to diagnose an individual patient when this is deemed necessary without prematurely reifying a category that has yet to pass its risk-benefit test and might have unfortunate unintended consequences.

3) The condition is subthreshold to the specific criteria sets, but nonetheless causes obvious clinically significant distress or impairment. There is no bright line between mental disorder and normality. The decision whether a mental disorder is or is not present inherently has to be made on a case by case basis. The NOS categories provide needed flexibility in diagnosing the many people who present at the boundary with normality. Clinicians can use the appropriate NOS category for the early diagnosis of subthreshold conditions (e.g. "prepsychotic risk") when this clearly warranted for that particular person. This is far preferable to introducing a specific category for "psychosis risk" that would inevitably misidentify many individuals who would be much better off without diagnosis and treatment.

4) The condition presents a mixture of symptoms from different specific disorders that are individually subthreshold but jointly causative of clinically significant distress or impairment. The proposal for a Mixed Anxiety Depressive Disorder is a perfect example and is best handled as an NOS. If made an official category, it would immediately become one of the most popular diagnoses in DSM-5 without any proof that treatment would provide more good than harm for the millions of people who would get the diagnosis.

In all these ways, the NOS categories are indispensable. They should be celebrated, rather than denigrated, and used whenever they are the best description of the less than typical patient. The designation NOS is never really nonspecific or noninformative because it places the patient in a suitable section of the manual without providing more certainty or specificity than the situation allows.

Advice to DSM-5:

1) Accept the fact of life that a certain degree of diagnostic uncertainty and heterogeneity is inherent in the definition of mental disorder. Do not seek to attain an unattainable and pseudoprecise total specificity.

2) Appreciate that each NOS designation provides considerable information (for example, Psychotic Disorder NOS is very different in its treatment and prognostic connotations from Mood Disorder NOS or Eating Disorder NOS).

3) List the most common examples under each NOS category and allow these to be subtypes of that NOS (e.g., "Eating Disorder NOS, binge eating presentation" or "Mood Disorder NOS, premenstrual dysphoric presentation."

4) Clinicians using the NOS diagnoses are dealing with nonprototypical boundary cases. They must therefore be especially careful in determining that the presentation is accompanied by sufficient clinically significant distress or impairment to warrant a diagnosis of mental disorder.

5) Do not create new diagnoses in a vain attempt to replace NOS. The suggestions for new DSM-5 diagnoses should instead be available as examples under the most appropriate NOS ("minor neurognitive" under Cognitive Disorders NOS, etc). There are two exceptions among the proposed new diagnoses -- "paraphilic coercive" and "hypersexuality" -- both of which are harmful constructs whose use should be discouraged altogether, even within the NOS rubric.

NIMH vs. DSM 5: No One Wins, Patients Lose