Over the years I’ve done quite a bit of professional development for teachers. This generally takes the form of a day-long conference where I hold sway for six hours with a break for lunch. I have had as many as 200 people in attendance, but it works best with about 80 teachers sitting in groups around tables. Since I’m known for hands-on science, I direct the groups in lots of activities.  We do quick fun “bets” based on science; we make paper; we make tops and spin them; we test various lipsticks; we taste and test ice cream and solve problems. There’s a lot of laughter and conversation. I get very high evaluations. People seemed pleased and satisfied and they all have at least one or two things they can show their students the next day. I am well-compensated for my time, and it is certainly an ego boost to be wanted. But, I have come to believe that this format for professional development is a BIG waste of time and money.

We do quick fun “bets” based on science; we make paper; we make tops and spin them; we test various lipsticks; we taste and test ice cream and solve problems. There’s a lot of laughter and conversation. I get very high evaluations. People seemed pleased and satisfied and they all have at least one or two things they can show their students the next day. I am well-compensated for my time, and it is certainly an ego boost to be wanted. But, I have come to believe that this format for professional development is a BIG waste of time and money.

Why? I don’t believe that much of what I say or do trickles down into what happens in these teachers’ classrooms. Maybe a few of them will use my books and pass on some of the activities. But I don’t hold my breath. The real reason that this is a waste is that much of what I talk about is NOT about what they have to teach the next day or the next week. And I give them so much new material, it is impossible for them to even begin to process it from a one-shot exposure, let alone internalize it and make it their own. One of the most important aspects of good pedagogy is timing—taking advantage of a teachable moment, or creating one so that the student is engaged and has reason to try doing something new. As a professional development consultant for teachers, shouldn’t I also be a model for such best practices?

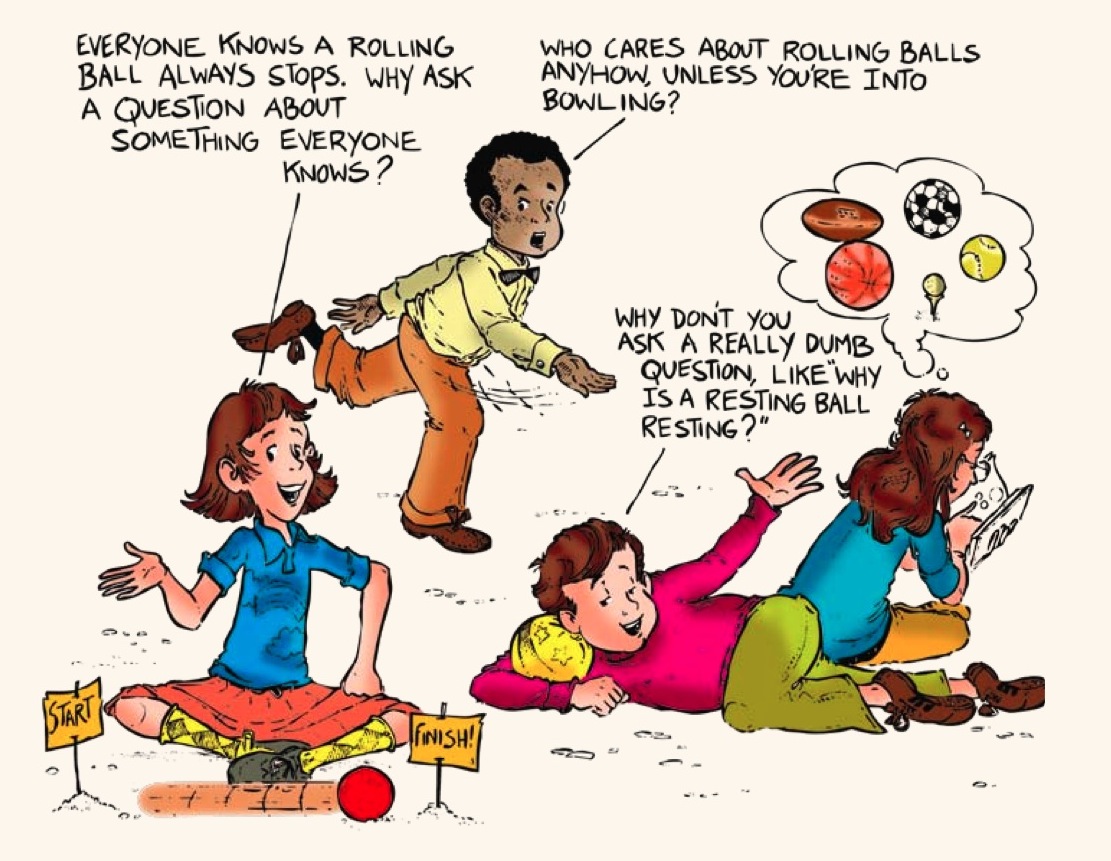

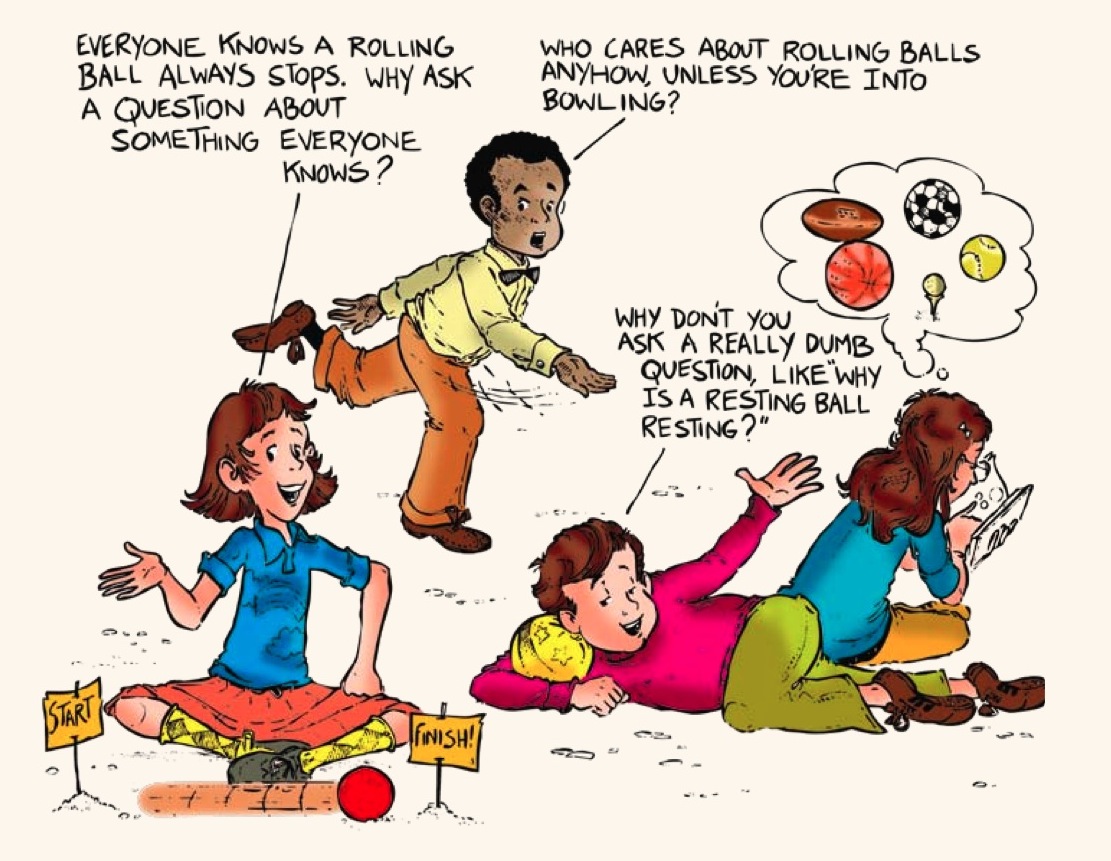

I wouldn’t be writing this if I didn’t have an innovative solution. The best instruction for professional development is mentoring where a seasoned veteran practitioner is available at critical moments to guide the learning. It also helps if the veteran can give the mentee some help in planning a sequence of lessons. Recently, I saw how this could work with two third-grade teachers, Carla Christiana and Alicia Palmeri, who have to teach a unit on the solar system as part of our Authors on Call pilot project. I first met with them via videoconferencing to plan. I used the time to get them to understand that how we know about the solar system starts with observing two things in the night sky: light (bodies of light) and motion. That’s it. So it was important they begin the unit with their students by thinking about motion. I suggested that they give their students a pdf of the first question in my book What’s the BIG Idea?, which uses inquiry to understand motion, energy, matter and life (four BIG ideas.) That question is, “Why does a rolling ball stop rolling?” I wanted their students to think about the question, discuss it with other students and take it home to share with their parents.

I suggested that they give their students a pdf of the first question in my book What’s the BIG Idea?, which uses inquiry to understand motion, energy, matter and life (four BIG ideas.) That question is, “Why does a rolling ball stop rolling?” I wanted their students to think about the question, discuss it with other students and take it home to share with their parents.

After a day of not knowing the answer, they could then start to learn the concept. (Interestingly, I recently read that a Eric Mazur, a Harvard physics professor, is also using this technique with his classes.) Becoming invested in a question motivates students to learn more. This kind of teaching was an eye-opener for my mentees.

After a day of not knowing the answer, they could then start to learn the concept. (Interestingly, I recently read that a Eric Mazur, a Harvard physics professor, is also using this technique with his classes.) Becoming invested in a question motivates students to learn more. This kind of teaching was an eye-opener for my mentees.

Both Carla and Alicia were very intent on having their students write reports. But the traditional elementary research report on the solar system reliably produces an uninspired regurgitation of facts about the planets. I wanted the students to learn enough to make personally meaningful discoveries that could inform original writing. So I suggested that they send their students, working in pairs, to the NASA website and its extraordinary library of photographs of heavenly bodies, to look up different objects in the solar system. When they made a discovery from a picture that excited them, they were to report on that. One concern was that the writing on the site is by scientists for adults, not exactly third grade material. So I said, “Tell them that you don’t expect them to understand it, but to do the best they can.”

Carla and Alicia listened to me. (I should mention that in addition to videoconferencing, we’re communicating by writing via a wiki.) Carla wrote on the wiki: “After telling them that the site we are reading from was written by NASA and that some adults thought the text might be too hard to read, they took on the challenge and read with vigor throughout the research session. Students began to shriek with excitement at first glimpses of the photographs of their planets and were calling their partners over to their computers to show the interesting facts they discovered and pictures they found. Two groups realized that the same instrument was used to collect data on two different planets. I look forward to having more time to research tomorrow afternoon.”

Carla and Alicia told me that they had completely disregarded all their previous lesson plans for this unit and were astounded at the excitement real learning produces. What did we all learn?

• Scientists spend time thinking about questions and that’s where creativity lies in science.

• Research requires asking good questions, close reading, concentration, and challenging language, but discoveries make it extraordinarily rewarding.

• Don’t make decisions about challenging material for your students. Motivation to learn raises the bar on performance.

• If you want different outcomes in learning you have to do things differently and this means taking risks.

• And last, but not least, learning is not just for third graders but for teachers and this mentor as well.

Obviously, the time I spent working with Carla and Alicia was a lot less than a day. But the suggestions and coaching came at exactly the right times over a period of weeks. The results, which speak for themselves, are transformative.

We do quick fun “bets” based on science; we make paper; we make tops and spin them; we test various lipsticks; we taste and test ice cream and solve problems. There’s a lot of laughter and conversation. I get very high evaluations. People seemed pleased and satisfied and they all have at least one or two things they can show their students the next day. I am well-compensated for my time, and it is certainly an ego boost to be wanted. But, I have come to believe that this format for professional development is a BIG waste of time and money.

We do quick fun “bets” based on science; we make paper; we make tops and spin them; we test various lipsticks; we taste and test ice cream and solve problems. There’s a lot of laughter and conversation. I get very high evaluations. People seemed pleased and satisfied and they all have at least one or two things they can show their students the next day. I am well-compensated for my time, and it is certainly an ego boost to be wanted. But, I have come to believe that this format for professional development is a BIG waste of time and money.Why? I don’t believe that much of what I say or do trickles down into what happens in these teachers’ classrooms. Maybe a few of them will use my books and pass on some of the activities. But I don’t hold my breath. The real reason that this is a waste is that much of what I talk about is NOT about what they have to teach the next day or the next week. And I give them so much new material, it is impossible for them to even begin to process it from a one-shot exposure, let alone internalize it and make it their own. One of the most important aspects of good pedagogy is timing—taking advantage of a teachable moment, or creating one so that the student is engaged and has reason to try doing something new. As a professional development consultant for teachers, shouldn’t I also be a model for such best practices?

I wouldn’t be writing this if I didn’t have an innovative solution. The best instruction for professional development is mentoring where a seasoned veteran practitioner is available at critical moments to guide the learning. It also helps if the veteran can give the mentee some help in planning a sequence of lessons. Recently, I saw how this could work with two third-grade teachers, Carla Christiana and Alicia Palmeri, who have to teach a unit on the solar system as part of our Authors on Call pilot project. I first met with them via videoconferencing to plan. I used the time to get them to understand that how we know about the solar system starts with observing two things in the night sky: light (bodies of light) and motion. That’s it. So it was important they begin the unit with their students by thinking about motion.

I suggested that they give their students a pdf of the first question in my book What’s the BIG Idea?, which uses inquiry to understand motion, energy, matter and life (four BIG ideas.) That question is, “Why does a rolling ball stop rolling?” I wanted their students to think about the question, discuss it with other students and take it home to share with their parents.

I suggested that they give their students a pdf of the first question in my book What’s the BIG Idea?, which uses inquiry to understand motion, energy, matter and life (four BIG ideas.) That question is, “Why does a rolling ball stop rolling?” I wanted their students to think about the question, discuss it with other students and take it home to share with their parents.

After a day of not knowing the answer, they could then start to learn the concept. (Interestingly, I recently read that a Eric Mazur, a Harvard physics professor, is also using this technique with his classes.) Becoming invested in a question motivates students to learn more. This kind of teaching was an eye-opener for my mentees.

After a day of not knowing the answer, they could then start to learn the concept. (Interestingly, I recently read that a Eric Mazur, a Harvard physics professor, is also using this technique with his classes.) Becoming invested in a question motivates students to learn more. This kind of teaching was an eye-opener for my mentees.Both Carla and Alicia were very intent on having their students write reports. But the traditional elementary research report on the solar system reliably produces an uninspired regurgitation of facts about the planets. I wanted the students to learn enough to make personally meaningful discoveries that could inform original writing. So I suggested that they send their students, working in pairs, to the NASA website and its extraordinary library of photographs of heavenly bodies, to look up different objects in the solar system. When they made a discovery from a picture that excited them, they were to report on that. One concern was that the writing on the site is by scientists for adults, not exactly third grade material. So I said, “Tell them that you don’t expect them to understand it, but to do the best they can.”

Carla and Alicia listened to me. (I should mention that in addition to videoconferencing, we’re communicating by writing via a wiki.) Carla wrote on the wiki: “After telling them that the site we are reading from was written by NASA and that some adults thought the text might be too hard to read, they took on the challenge and read with vigor throughout the research session. Students began to shriek with excitement at first glimpses of the photographs of their planets and were calling their partners over to their computers to show the interesting facts they discovered and pictures they found. Two groups realized that the same instrument was used to collect data on two different planets. I look forward to having more time to research tomorrow afternoon.”

Carla and Alicia told me that they had completely disregarded all their previous lesson plans for this unit and were astounded at the excitement real learning produces. What did we all learn?

• Scientists spend time thinking about questions and that’s where creativity lies in science.

• Research requires asking good questions, close reading, concentration, and challenging language, but discoveries make it extraordinarily rewarding.

• Don’t make decisions about challenging material for your students. Motivation to learn raises the bar on performance.

• If you want different outcomes in learning you have to do things differently and this means taking risks.

• And last, but not least, learning is not just for third graders but for teachers and this mentor as well.

Obviously, the time I spent working with Carla and Alicia was a lot less than a day. But the suggestions and coaching came at exactly the right times over a period of weeks. The results, which speak for themselves, are transformative.