It seems that there’s a lot of jargon out there in educational circles. I feel really dumb when I’m sitting in a group and I don’t understand the terminology. One of the concepts I recently heard bandied about is “scaling up” as it applies to best practices. It took me a while to figure out what that means. I think it means looking at research to find out what works in a study and then somehow mass-producing it so that everyone benefits.

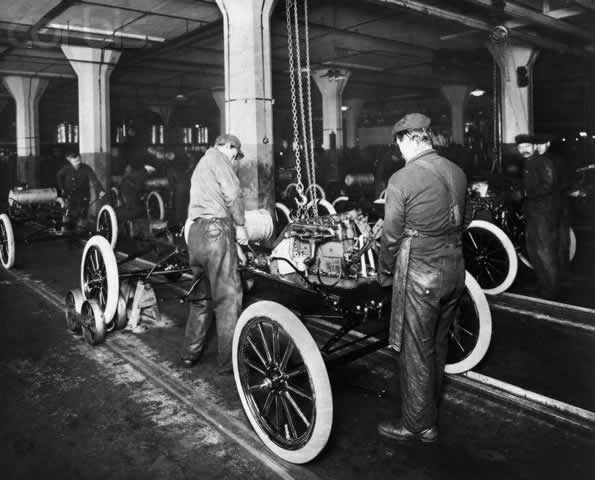

The innovator of “scaling up” in American history was Henry Ford. He figured that mass-producing cars would lower the price, so he invented the assembly line. Not only was this an efficient method for building cars, but also the price was low enough to create a market for them. Each of his workers did one job and collectively they constructed a complicated machine that even they could afford to buy.

Factories for building all sorts of things were ubiquitous and the industrial revolution took another giant leap forward. In addition to creating a consumer society, the industrial revolution transformed public education to produce factory workers — people who could read and follow directions and knew how to get along with others. The rising standard of living produced a middle class who derived pleasure and fulfillment from after-work leisure activities that they could now afford; fun was not something they expected during the workday. No one seemed to question the fact that factory work was tedious and dull.

Fast-forward to the present. Inventive as we are, we began building machines to take over the tedious, repetitive jobs of the factory worker. Robots are far more compliant than workers in unions. This led to fewer factory workers but opened up opportunities for more highly trained individuals to keep the robots in working order. (The tedious factory jobs are also being shipped overseas.) Now the President has said that jobs of the future require innovators, creative types; we need problem solvers to move our society forward (and maintain the robots).

I’m an outsider, belonging to no institution or school (although I visit lots of schools as an author). I’m trying to make sense of what I see happening among the powers-that-be who are determining the course of American education, particularly at the elementary school level.

Here’s a parable on how I see it: The clarion call goes out from on high that our schools need to mass-produce “problem solvers.” Education professors go to work deconstructing “problem solving” to figure out the steps needed to teach it. Naturally, several diverse approaches are identified. Books are written and studies are published about the best practices so that “how to teach problem solving” can be “scaled up” for teachers. Competing publishers claim that their books are the best ones to teach this skill to kids. Tests are devised to measure “problem-solving ability” in students, putting teachers in a panic that they’re not effectively following the guidelines on how to teach problem solving. We now have an industry employing lots of people working on the problem of how to scale up teaching problem solving, yet the tests show that our kids are falling short.

I think you can see where I’m going with this: If we want to teach problem solving, why not give kids real problems to solve? You might be surprised at how inventive and creative kids can be, especially in kindergarten before they’re taught conformity and a factory mentality has taken over. Perhaps producing problem solvers has to be handcrafted, one child at a time. Perhaps we’re being sold the idea that a single source is the formula for teaching how to produce problem solvers by the people who are mass-producing that source. (They l$ve the idea of scaling up.)

The same thing is true for the teaching of “critical thinking.” Why not give kids two reading assignments on the same subject? Then ask them which one they liked better and why. We’d now be teaching critical thinking while teaching content. And while we’re at it, shouldn’t teachers be allowed to think critically? Shouldn’t they be allowed to challenge the methods being imposed on them by administrators? In “scaling up” instruction methods in the classroom are we are turning teachers into robots? What behaviors are these teachers modeling for the future scientists, engineers and innovators in their class?

So far, we haven’t invented a machine to replace higher order intellectual skills. But in the interim it seems to me that our efforts to “scale up” are beating these very qualities out of our classrooms for both teachers and students. Isn’t “individualism” one of our bedrock American cultural values?

In this post I’m simply asking questions that just might pose a problem to be solved.