When it comes to genres in children's literature, I long ago accepted that mine is a stepchild. I write nonfiction for kids, stories about the real word and hands-on activities in science. I've written so many activity books, beginning with "Science Experiments You Can Eat," that I've been called the "Julia Child of hands-on science." My work has been recognized and rewarded by people who read children's literature for a living -- children's librarians. And in the past three years, I've joined with other award-winning nonfiction authors in a group blog: Interesting Nonfiction for Kids (INK), which is gaining traction and notice in the educational community. Yet our books hardly ever find their way into many classrooms where they can do the most good. There are all kinds of reasons why they aren't used, but there is a compelling argument that connects the dots. Naysayers take note. Here's why I think books by award-winning nonfiction authors can save education (and teachers can keep their jobs):

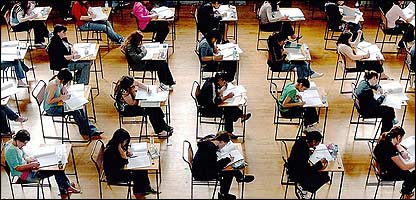

Teachers are living in fear these days. Their administrators are equally fearful. The reason: ASSESSMENT TESTS. And why are their knees shaking so hard? If students don't measure up, a school's reputation suffers, real estate values in their district suffer, taxes go down, there is less money for education, school budgets must be cut and people (teachers and administrators) can lose their jobs. So everyone frantically focuses on THE TESTS.

The top educators have been thinking long and hard about what kids need to know. Each district/state, even the nation has developed standards and content strands -- the so-called scope and sequence of what kids need to know and when they need to know it. They make their scope and sequence -- their lists -- available to the public and to the people who create educational materials, including textbook publishers and others who produce product for the very lucrative (and highly competitive) school market. These publishers take the lists as written, use them as outlines and hand them to writers. "Cover this material" are their instructions. And their efforts are there for all to see in heavy tomes, in wikipedias, and in Google search results.

The expository prose created in this way is flat at best and positively boring and insulting to the reader at worst. How do I know? I was once asked to write a textbook and was handed THE OUTLINE. Yes, I can write a decent declarative sentence. I'm not a bad speller and I know the rudiments of punctuation. But, much as I needed the money, I turned down the job. Why? I told them that I don't write their way. I tried to 'splain it to them (as Desi Arnaz would say): They could hire Shakespeare and give him THE OUTLINE to follow and they might get something they'd want to publish, but they wouldn't get Shakespeare. They didn't get it. I moved on.

Meanwhile the test creators are cooking up THE TESTS. One of their main focuses is on reading comprehension, of which 50 to 85 percent is nonfiction. A typical question involves giving kids three or four paragraphs to read and then asking them about what they've just read. But the test manufacturers aren't hiring writers to create these paragraphs. They are searching high and wide for samples of excellent writing -- literature -- so that they can write questions like "What is the author's point of view?" And just where are those test makers finding their writing samples? Are you ready for this surprising insight? FROM OUR BOOKS!!!! How do I know? I have a file full of permissions I've granted to test publishers over the years as do my INK colleagues.

So my question to educators is: Why teach from inferior reading materials to prepare for tests that are based on literature? Why not teach from our books in the first place? How can kids develop the critical thinking skills to answer questions like "What is the author's point of view?" when they are learning from materials where the author has no point of view? This is particularly true of reading in the content area -- science, math and social studies. Don't you get that "covering" the material is not the same as teaching it?

There's a leap of faith here that must be taken. I've read the standards. They are NOT LIMITING. There's a lot of room for many voices, a myriad of approaches, and a variety of topics within curriculum guidelines. EVERY STUDENT DOESN'T HAVE TO LEARN EXACTLY THE SAME CONTENT. (Not that every student ever did). Education is not about an assembly line approach. Each child is hand-crafted. It's about respect; respect for the learner and respect for the teacher. A formulaic, limited, strict interpretation that becomes simply teaching to the test doesn't respect either. And that's what sets literature apart. We authors have nothing but respect for our readers. We assume that the children we write for are intelligent human beings capable of comprehending the subject matter that gets us excited. The evidence is there in every sentence we write. And if you're worried about meeting the standards, use our free database, with each book aligned to the standards by the authors themselves who have a deep understanding of how their work fits into these broad definitions.

So my challenge to educators is to abandon the training wheels of prescribed texts. Do what the high-scoring schools have done for years. Liberate your teachers. Use our books to bring the joy of learning back into the classroom. Believe that learning happens when kids are engaged. Then, give them a few practice tests the week or so before the big bad assessment tests. You might be surprised at the results and wonder just what all the fuss was about.