"When the nation is made ready by enlightenment, its good fortune will make Black History Month an anachronism. No culture should by its spotlight eclipse another, and the reputation of one cannot flourish at the expense of another. We are a unified but not yet united civilization."

--Ron Issacs

In 1991, the phenomenon of unearthing 400 enslaved Africans from a 17th-century African burial ground in lower Manhattan was the beginning of a search by many for their African ancestral past. That road of discovery has had many twists and turns. However, the records remain. The slavers and historians of that era kept copious notes. And fortunately we have had access to the incalculable research from the African Burial Ground Project OPEI Update founded in 1991 and directed for over a decade by Dr. Sherrill Wilson.

If we take another look at life in colonial New York and search beyond the Dutch West India Company's enticement of free land and free trade, we will see that the DWI Company provided another enticement to white settlers: enslaved Africans to labor without compensation. In the East India Company's charter of Privilege and Exemption for the patrons the following is noted: "in that document for the purpose of encouraging agriculture, the company agreed to furnish colonists as many blacks as they conveniently could. These 'blacks' were brought from the West Indies."

The Historic Wyckoff House, which is located in Brooklyn, N.Y., is an example of colonial life in early New York. A recent article: "Glimpse the 17th Century at Historic Wyckoff House," describes the property as one that spanned 40 acres. It was also viewed as a property that was a highly successful working farm. Wyckoff, its owner, became the richest man in the region. It may also be noted that: "Slaveholdings in New York were second only to its counterpart in Charlotte, North Carolina."

The Native Americans and Africans helped make the Dutch wealthy land barons as they farmed large areas, working fruit orchards and attending the livestock for food. Flax was grown for linen thread and sheep provided wool for clothing. A visit to Philipsburg Manor Upper Mills today in North Tarrytown will provide additional insight into the lifestyle of the Dutch gentry of this period. This site was manned by enslaved Africans as the Philipses reaped the reward from this free African labor.

Bland Taylor writes: "in 1698, 15 percent of Kings County population were slaves. Kings County by the 18th Century became the heaviest slave holding county in New York State. Although one-fifth of New York State black population were free by the end of the 18th Century only 3 percent (46) free blacks resided in Kings County, the smallest number in the state.

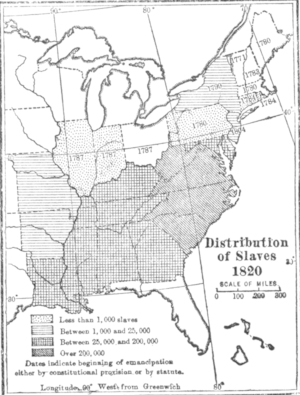

As late as 1820, only 55 percent of Kings County blacks and a minuscule 18 percent in Richmond County were free. Blacks older than 45 years remained slaves in 1820, because masters were unwilling to accept responsibility for their maintenance otherwise. Slavery in the United States existed in the North as well as the South."

What is unique about Scarsdale is the heroic effort of New York Governor Daniel Tompkins, a resident of Scarsdale, as he made a recommendation to the Legislature in 1817 to abolish slavery by 1827. We can also witness the courage of the Quakers who manumitted their enslaved Africans by 1782 and even required themselves to train their former slaves to earn a living and to find a place to live. And we can witness the beneficence of Quakers who were active in the Underground Railroad, hiding slaves in barns and secret cupboards on Mamaroneck Road.

Racism today is merely a remnant of slavery's past revisited in the present. Today, we have two separate chronicles of history: one white and one black. Yet, the two belong together.

Understanding our true past will enable one to understand the present. However, the care of the future is in our hands.

Yes, Ron Issacs, "When the nation is made ready by enlightenment, its good fortune will make Black History Month an anachronism."