The Senses: An Exhibit That Provokes Beyond Vision

By Karen Kraskow

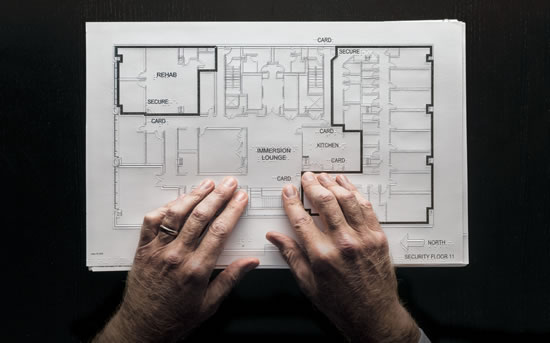

Tactile Architectural Drawing, 2015; Mark Cavagnero Associates with Chris Downey for Lighthouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired. (© Don Fogg)

Can we see beyond what sight brings us in touch with? This is the premise of the exhibit at the Cooper Hewitt Museum called “The Senses: Beyond Vision,” that indeed we can, and we need to, in different ways. It all depends on our strengths — and lesser strengths — in our different senses. Every human being has different and varying levels of capacity in tasting, touching, smelling, seeing, and hearing. Through design, the exhibit claims, we can develop different languages of form and function that incorporate awareness of these differences, moving closer to the goal of including all users.

Let’s take a look at what happens when there’s a loss in the level of hearing. Hansel Bauman, architect of Gallaudet University, a college in Washington, D.C. that serves students who are deaf, writes about how he designed the interior to encourage communication, socialization, and way-finding (“DeafSpace,” in The Senses: Design Beyond Vision).

Many users communicate with sign language (American Sign Language) that requires more space among users, if say, they’re walking down a corridor. So Bauman created wider ramps where pedestrians can walk and sign in spatial comfort. When a communicator is seated at a table and wishes to engage in conversation with someone at another table, who may be facing away, a tap on the floor, causing it to vibrate, can alert him or her of the desire to chat. A tap or slight pressure on furniture can accomplish the same goal. Visual cues created by a reflective surface at the end of a corridor can indicate to walkers the presence of someone coming behind them … or walking down a connecting corridor about to turn toward them. Desk arrangements support visual interaction, enabling seated members to see each other’s faces, make eye contact, sign and thereby be more productive, collegial and engaged with each other. Lastly, when communicating through sign or even without, it is advisable to converse in a space where one is positioned before a solid wall rather than a backlit surface — such as a window — that would tend to make a silhouette of the person, thus making it difficult to see hand movements or facial expressions. Light blue and green walls are particularly good because they contrast with most skin colors.

Another useful tool that we can form an effective response to is the cane that was designed for users whose level of sight is limited, perhaps not available to any degree. It’s a challenge ... to navigate a city, to reach your destination safely. Extending the power of the mobility cane, architect Teddy Kofman (then a professor at Cooper Union) and his students developed a proposal of tactile paths for city streets... that would use texture underfoot at intersection points that led to a building, a bus stop, an information panel, etc. A language of texture was developed - one texture for a building entrance, one for a mode of transportation, one for a bench, etc. so that the walker would know where to turn off to reach their destination. Construction sites, which might arise without one knowing in advance, would include a widening of the tactile path on the ground surface when they began, sound indicators on barriers surrounding them telling the pedestrian that a turn was up ahead - and then the distance till the next one - thus combining the use of multiple senses to guide one safely around the temporarily constructed work area. A video animation of pedestrians walking around a construction site with these sense-expanding tools added to them is on display in The Senses: Beyond Vision, stimulating our development of sensory vocabulary and tools to apply in our lives, in situations we may not yet consider for ourselves and for any situation we find ourselves or our loved ones in. This life-enhancing, thought-reconfiguring exhibit runs until Oct. 28. #

Karen Kraskow, M.A., M.S.W. is a Learning Specialist in private practice in Manhattan, specializing in working with ‘reluctant writers,’ struggling readers, and mathematicians experiencing confusion and other hurdles. Karen studied industrial design at Rhode Island School of Design and Pratt Institute and is a member of the American Institute of Architect’s Design for Aging Committee. She can be reached at kkraskow@gmail.com.