BOOK REVIEW

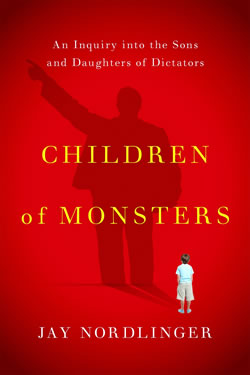

Children of Monsters: An Inquiry into the Sons and Daughters of Dictators

By Joan Baum, Ph.D.

Children of Monsters:

Children of Monsters:

An Inquiry into the Sons and Daughters of Dictators

By Jay Nordlinger

Encounter Books, 268 pp., $16.99 [orig. pub. 2015]

This may not be the kind of book to try to read in one sitting. What’s the cognitive equivalent of eyes glazing over that would describe taking in 20 chapters of accumulated horror, sadism and suspended morality by the children and sometimes grandchildren of pathological political leaders of the 20th and 21st century? Even if, as here, author Jay Nordlinger, senior editor at National Review, invokes a breezy, conversational style, interjecting into his unusual inquiry a personal, incredulous, often witty sense of disbelief.

Impressively, Nordlinger’s done extensive research, reading about and interviewing defectors, analysts, witnesses, friends, former friends. “I have used everything I can, everything possible: every scrap or remark or hint” — biographies, memoirs, histories, interviews. “Around dictators and their children, rumors swirl, of course . . . In my job as scavenger, I often asked, ‘What smells right?’ Your nose is an important organ in composing a book such as this.” He charmingly apologizes for relying on words such as “apparently, evidently, reportedly, seemingly,” but guesswork was inevitable, he says, though he deigns to draw conclusions from unverifiable hypotheses.

Though the book covers the progeny and the extent to which the children were chips off the old bestial block, it’s impossible to know how many children each dictator had. Not the conjugal or monogamous types, the dictators had multiple wives and many mistresses. A lot of information about their families, legit and illegit, remains unknown. Did Hitler have a child, and did that child have a child — both of whom, Nordlinger points out, look like him (check out chapter one)?

The list of infamous parents includes, in order and by region, Hitler, Mussolini, Franco, Stalin, Tojo, Mao, Kim, Hoxha, Ceausescu, Duvalier, Castro, Qaddafi, Assad, Saddam, Khomeini, Mobutu, Bokassa, Amin, Mengistu, Pol Pot. With pictures of each, sometimes with their fathers, tyrants’ children get space according to how “interesting” or “important” they are and how much can be learned about them. Svetlana Stalin gets a lot of attention because she wrote memoirs and because she has been written about, especially when she became an American citizen (she registered with the Republican Party and donated money to the National Review).

Nordlinger repeatedly notes that succession was only through the male line but that sons and daughters sometimes exerted great power, especially if they stayed on or remained tight lipped after their fathers had their siblings and in-laws killed (see particularly Edda Mussolini in Italy and two Hussein daughters in Iraq). Tellingly, as Nordlinger notes, mass executions did not dissuade most children from keeping the family name (recognition breeds power) or from declaring defensively, sometimes proudly, most always ambivalently, abiding love for their big-time murdering parent.

In the Foreword, Nordlinger says the idea of the book came to him in 2002 when he was visiting Albania for the State Department. Enver Hoxha had been the Communist dictator (and head of secret police) from 1944 until his death in 1985, a man who “achieved an almost perfect tyranny. No one could breathe.” Nordlinger got to wondering about what it must be like “to bear a name synonymous with oppression, murder, terror, and evil.” The idea percolated and so did his list of dictators, but he kept it to 20, adding or subtracting “a couple of brutes.” He notes also that the dictators “are not equal in their monstrousness . . . Mobutu of Zaire, for example, was an angel compared with his friend and neighbor Bokassa.” In the dictator business, Nordlinger sardonically adds, “we sometimes grade on a curve. Franco was a lamb compared with our genocidal monsters: Stalin, Mao, Pol Pot, et al.” In short, there were monster sons of monster fathers, such as Vasily Stalin, Nico Ceausescu, the Qaddafi, Assad and Saddam Hussein boys. But there was also a smattering of so-called “comparatively normal people” and a couple who did break away (Svetlana, and Alina Fernández, Castro’s daughter).

Nordlinger’s conclusion is that the children, historical footnotes, were / are nonetheless still human beings “born into a very strange position.” And so, he admits to writing a “psychological study” in part, even as he deigns to adjudicate between nature and nurture. Many of the children vacillate or deny, subject to opportunism, wealth, ambivalence, the perks of power, not to mention the influence of their fathers’ collaborators and of well-wishers from the grisly past.

Of course, the key questions are: Why the book and what should readers take away from it? Nordlinger reminds readers that he is reflecting on “the children’s hour,” not the tyrants themselves; that most of the children were “bit players on the stage of history”; and that denying one’s parents is difficult. Even Svetlana has fond memories. One should note, however, that in the three years since Children of Monsters was first published, North Korea and Syria have horrifyingly occupied the world stage in new ways and that Fidel is dead. Their chapters particularly, therefore, give pause. #