A Debate On The Pros And Cons Of Aging And Death

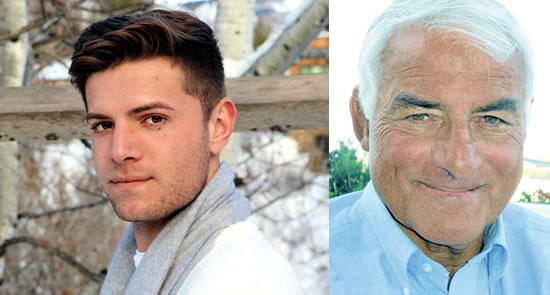

By Allen Frances, MD & Tyler Frances

(L-R) Tyler Frances & Allen Frances, MD

At age 74, I have already experienced many of the indignities of aging and before very long will also confront the inevitability of death. Although neither prospect is particularly pleasant, I strongly believe in the normality and necessity of both. Claims that science will soon prevent aging and dramatically prolong life strike me as irresponsible hype and false hope. I am all for efforts to expand our healthspan, but see little value in prolonging our lifespan, and little possibility that we will soon discover a fountain of youth.

My grandson, home from college for Christmas break, disagrees with what he regards as my sentimental and regressive attachment to the status quo. Tyler is participating in stem cell and genetics research and believes that it is feasible and desirable to double the human lifespan and make aging just another curable disease. Tyler has no qualms about this research and regards my doubts as technically naive and ethically unnecessary.

Here is a very brief point by point summary of our ongoing debate.

Me: Evolution requires aging and death to make room for each new generation and also favors a fairly rapid succession of generations. Both are necessary to provide raw material for the variability and beneficial mutations essential to natural selection.

Tyler: Evolution has little interest in aging and death. Natural selection focuses its selective pressure on producing optimal reproductive fitness in the mating members of any species. Once the period of reproduction and weaning have passed, natural selection applies much less pressure on how the rest of the lifespan plays out. There is thus no inherent evolutionary reason to prohibit research that would prevent aging and prolong life. And there are excellent reasons to pursue it- although evolution does a remarkable job when given enough time, it works far too slowly and imperfectly to help us solve our current problems. Whenever, in the past, it has served our interests, humans have always felt free to speed up natural selection. We would still be hunters and gatherers were it not for the artificial selection of domesticated plants and animals that constituted the agricultural and pastoral revolutions. If we have the genetic tools to promote human health, longevity, and happiness, why not use them.

Me: But the world is already terribly over-populated and is rapidly becoming even more over-populated. Extending the lifespan will mean more crowding, more mouths to feed, more environmental degradation, and more resource depletion. Malthusian dynamics ensure that providing a longer life for some must be purchased at the high cost of a more brutal life for the many- a life threatened by even more wars, migrations, famines, and epidemics.

Tyler: Overpopulation is best solved by reducing birthrates. This has already been done with great success almost everywhere in the world except Africa and the Middle East. It will be a better, more mature, and healthier world if people live longer and have fewer diseases and fewer children. A longer lifespan will make people wiser, more future oriented, and less willing to take foolish risks in the present. This could lead to more rational decisions on how best to preserve our planet as a decent place to live.

Me: Only the rich will be able to afford new products that prevent aging and promote longevity. The resulting caste system based on lifespan will be even more unfair than our current divisions based on wealth and power.

Tyler: The distribution of benefits that will accrue from aging research is a political, economic, and ethical question, not a scientific one. Given human nature and existing institutional structures, the benefits will almost certainly be enjoyed in a markedly unequal and unfair fashion- greatly favoring the rich and powerful, with only a very slow trickle down to the population at large. This inequity has accompanied every previous technological advance in the long march of human progress and is not specifically disqualifying to progress in slowing aging and death.

Me: Every scientific advance can, and usually does, have harmful, unintended consequences (medical, social, political, economic) that cannot possibly be predicted in advance. Scientists always have intellectual and financial conflicts of interest that bias them to exaggerate the potential benefits to be derived from their discoveries and to minimize the potential risks.

Tyler: Surely, aging research will have its hype, blind alleys, and unexpected complications- these are an unavoidable risk in all scientific advances. But the risks and difficulties should not paralyze efforts to make the advance or call into question whether it should be made; instead, they should increase caution and vigilance in how it is done. And we must remember the context. Our world is already going to hell in a handbasket- the risks of advancing science are real, but the potential benefits may be all that stand between us and disaster. Science is necessarily disruptive, but may offer our only road to salvation. To quote Mark Watney in the movie ‘The Martian’: “In the face of overwhelming odds, I’m left with only one option, I’m gonna have to science the shit out of this.”

Me: There is something arrogant and unseemly about tampering with anything so fundamental to life as aging and death. Their inevitability has always been an essential element governing the ebb and flow of all the species and all the individual organisms that have ever lived on our planet. Why assume that we have the right, or the need, to tamper with such a basic aspect of nature?

Tyler: Scientific progress has always challenged conservative values based on a sentimental attachment to the past. My grandfather would probably have worked hard to convince the first agriculturalists that they were breaking some sacred and natural code when they chose to settle down in one place rather than continue following the hunt. There is no inevitable, inexorable, over-riding, and natural law defining and governing one correct path of human destiny.

Me: Curing disease is the primary goal of medical science. But aging is not a disease- it is an entirely expectable wearing down, an expression of biological entropy that cannot be reversed. We should certainly target the diseases that occur in old age in an effort to extend the average human healthspan. Success will improve the well being of the elderly and have a small subsidiary effect on lifespan- eg, more people living into their 80’s, 90’s, and 100’s. But we should not expect that better treatment for diseases will allow people to live to biblical ages. Despite the hype to the contrary, there is no reason to believe it is scientifically feasible or ethically desirable for people to stay young for 150 years. The most compelling lesson of scientific research is that the body is far more complicated and intricately balanced than we could possibly imagine.

We are still at a very early stage in curing disease- there is no reason to think we can prevent decline or postpone death.

Tyler: It is far too early to tell whether aging in humans is more a reversible disease or an inescapable degenerative process. But since aging is caused by biochemical processes, it most likely can be prolonged by biochemical interventions. We can’t decide the question based on values and reasoning- only by actually doing the aging research will we learn whether aging is preventable. And sure it may take many decades, but that’s precisely why we have to allocate the resources now to get the project off to a fast start.

Me: Unrealistic promises result in false incentives and misallocated resources. Typical example: we are investing a vast fortune on the wildly unrealistic goal of eliminating dementia within a decade or two, while taking dreadful care of the people who are already actually demented. Less hype would result in better balance between our hopes for the future and fulfilling our responsibilities in the present.

Tyler: Aging is already a pressing current issue and will soon become the biggest medical problem of our future. There is no running away or putting our head in the sand. My goal is to make life longer and better for people. Sure, there are some aging researchers who are overly enthusiastic in promoting their research and in promising quick results. And we mustn’t neglect the many practical problems of people who are aging today on the false hope that science will quickly and magically come to their rescue. We must find a proper balance between research investments that will pay off only in the distant future and current health care investments for those who are in need today. The future of our species depends on how we handle our demographics. The way ahead is difficult and uncertain- but that has never stopped us before. We make lots of mistakes along the way, but science helps us correct them. There is no standing pat- if we don’t move forward, we will move backward.

My Reflections On The Debate

There is a disturbing myth from ancient Greece. Aurora, the immortal goddess of the dawn, falls so deeply in love with a mortal man that she cannot accept losing him to death. She pleads successfully with the Olympian gods to grant him immortality, but forgets to request that he also be gifted with perpetual youth. Her human lover Is thus punished with the worst of fates- interminable life, daily made more intolerable by progressive aging and deterioration. Jonathan Swift illustrated the same chilling issue in Gulliver’s Travels and also tragically in his own long, tortured, and undignified death from dementia.

Modern medicine has cursed an increasing percentage of our aging population to suffer this miserable fate- an artificially prolonged life preventing a natural and peaceful death. Medicine is, so far, much more advanced in keeping elderly people alive than in keeping them well. Our goal should be enhanced health, not a longer existence if that existence is painful and has lost all meaning. Medicine should help people live well, but also let them die peacefully and with dignity.

Tyler is much more optimistic than I that we will soon have the technical means to prolong youth and postpone death- and that we should use them. I am more accepting of the limits of life- eager to improve its quality, rather than expecting to extend its duration. Tyler trusts scientists to make scientific decisions. I believe that scientists have conflicts of interest that make them uniquely unqualified to judge the ethical implications of the scientific opportunities open to them. If scientists can do something, they will do it- fairly heedless of unintended consequences. Tyler has the optimism and enthusiasm of the young. I have the pessimism and caution of the old.

In a final flourish, Tyler trumped my argument that aging and death are somehow natural to the evolutionary scheme of things with the paradox that evolution has also given us the power to control aging and death and that surely we are programed to use it.

He is probably right. I don’t think our debate will be settled on ethical or theoretical grounds. History provides precious few examples of a society voluntarily rejecting the application of a powerful new technology- e.g., China burning its navy in the fifteenth century; Japan banning guns in the seventeenth. But both were closed societies whose conservative decisions were governed by internal political concerns; they were much less responsive than ours to economic and scientific competition and pressure.

My guess is that scientists will be given the freedom and the funding to follow every possible path to the fountain of youth and to doubling the lifespan.

If they succeed, some chosen few of humanity will enjoy great benefits, while the masses may suffer even more than they do today and our environment may decay even faster than it already has. But I find aesthetic comfort in the firm belief that the scientists won’t be able to deliver on their extravagant promises. Although our knowledge base is increasing exponentially, the more we learn about the body, the more we appreciate how difficult it is to translate basic science into clinical application. Our bodies are remarkably complex and carefully balanced machines. Scientists can tinker with them, but I suspect that the basic cycle of life and death will be very hard to change. #

Allen Frances was the former chair of Department of Psychiatry, Duke University. Tyler Frances is a freshman at Harvard.