INTERNATIONAL EDUCATION

Art That Heals: Extraordinary Embroidery by the Even More Extraordinary Women Who Make It in Rwanda

By Juliana Meehan

I came to Rwanda in 2010 as a tourist and educator; I left a curator of art.

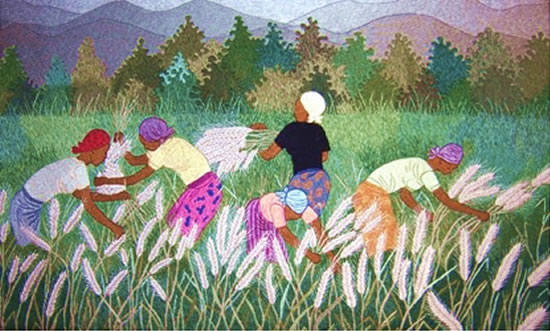

In between excursions to the rainforest for birding, the savannah for safari, and the Virunga Mountains for an afternoon with a family of silverback gorillas, I walked into a tourist shop in the capital city of Kigali and laid eyes on an exquisite piece of textile art: brightly clad women harvesting wheat with rolling hills and jigsaw-puzzle trees in the distance.

I had to view it close-up to confirm that it was, indeed, composed of thread and not paint. I bought it on the spot. And then I saw another, a man and a woman picking coffee; and then there was the tiger; and the grey-crowned cranes; and then the giraffe that looked like Rwanda’s nod to Gustav Klimt. Despite the fact that my husband John had by then broken into a cold sweat, I bought every one in the store with the exception of one that was too big for the plane.

“You like them so much,” said the shop owner, a stately Rwandan woman by the name of Christiane Rwagatare, “would you like to see how they’re made?”

A few days later John and I found ourselves in Christiane’s jeep bouncing along a dirt road on our way to the village of Rutongo, up the mountain from Kigali, eager to see the art in process. There, in a small house of whitewashed cinder block, fifteen women sat with cloth spread across their laps, patiently, expertly creating vibrant embroideries.

There we learned the rest of the story. These women hailed from both sides of the genocide, and they had put the events of the past behind them to work together in the hope of a better future. Their workshop was begun by our guide, Christiane, who had lived most of her life in exile and who returned after the genocide with the intention of helping in Rwanda’s reconstruction.

This first workshop was started in 1997, and it was here in Rutongo that their embroidery techniques and style were developed and honed. It was here that they first learned to use three colors of thread in one needle to produce the nuanced shades that give their works depth and vitality. And it was here that they produced the award-winning compositions that are on permanent display in Rwanda’s National Art Gallery.

I returned to the States with a mission: to support their efforts by bringing these works to the attention of the American public. I immediately sent out emails and letters with pictures and captions to everyone I could think of: galleries, museums, local arts associations. Then, one afternoon about a month after returning from Rwanda, I opened up the New York Times arts section to see a photo of a large African carving and a review of a gem of an African Art museum in—of all places—Tenafly New Jersey. I taught middle school English in Tenafly New Jersey! Who knew there was an African Art Museum within a mile of my classroom? I called, rattled out the whole story in five minutes to the curator, Bob Koenig, and was graciously invited to bring some examples of the works to him. Immediately upon seeing them Koenig said, “Sure. We’ll give you a show.” And that was the beginning.

Since that very successful show at the SMA Fathers Museum of African Art in October of 2011, I have grown the exhibit and shown it to appreciative audiences in New Jersey, New York, Ohio, and Washington, DC. I call the exhibit PAX Rwanda, because it is the fruit of the reconciliation that has taken place among the women. I continue to look for a market and for funding to make their workshop self-sustaining, guided by the model of the Women of Gees Bend, self-taught poor women from the American South whose masterful quilts ended up in the Whitney Museum in New York.

We returned to Rwanda in July of 2016. Since then, the workshop has relocated to the village of Kabuye. Some of the artists I met in 2010 have moved on, and some new ones have joined the group. John and I spent a day taking their pictures and trying to get to know them a bit. Hearing their stories, twenty-two years post-genocide, it is immediately evident that no one’s life is untouched by those 100 days in the spring of 1994 in which one million Rwandans were killed, leaving ten times as many widows than widowers. In our workshop alone, some had lost husbands, others lost fathers, still others lost children.

Many Americans associate Rwanda only with the genocide; some as the place where one can view silverback gorillas in safety; some as pristine birding territory. The traveler to Rwanda actually comes away with something much more complex and beautiful, because all these things are inextricably interwoven.

Twenty-two years post-genocide, Rwandans are rebuilding their lives. This group of brave and talented women is rebuilding through art.#

Juliana Meehan is a teacher at Tenafly Middle School in Tenafly, NJ.